- Home

- Cynthia Hand

Boundless (Unearthly) Page 3

Boundless (Unearthly) Read online

Page 3

“Absolutely,” he says, and we get on either side of her and walk her slowly back to Roble.

“Thanks for helping me out tonight,” Amy says to me after she’s situated in her room with her foot wrapped tightly in an Ace bandage, propped on a stack of pillows with a bag of ice pressed to her ankle. “I don’t know what I would have done without you. You’re a lifesaver.”

“You’re welcome,” I say, and I can’t help a gloaty smile.

I did help her, I think later when I’ve gone back to my room. The sun is almost up, but Wan Chen isn’t back yet. I lie on my tiny twin bed and stare at the water damage on the ceiling panels. I want to sleep, but I’ve still got too much adrenaline in my system from using my power out in the open like that. But I did it. I did it, I keep thinking, over and over and over again. I healed that girl. And it felt amazing. It felt right.

Which gives me another crazy idea.

“I think I might want to go premed.”

Dr. Day, the academic adviser for Roble Hall, looks up from her computer. She has the grace not to look too surprised that I’ve burst into her office and informed her that I am contemplating becoming a doctor. She simply nods and takes a minute to pull up my schedule.

“If you’re considering premed, which is typically a straight biology or human biology major, we should get you enrolled in Chem 31X,” she says. “It’s a prerequisite for most of the other biology courses, and if you don’t take it this fall, you’ll have to wait until next fall to start the core classes you’ll need.”

“Okay,” I say. “I like chemistry. I took College Prep Chemistry last year.”

She looks at me from over the top of her glasses. “This course can be a little hard-core,” she warns me. “The class meets three times a week, and then there’s a biweekly discussion session led by a teaching assistant, plus another couple hours a week in the lab. The entire biology track can be fairly high intensity. Are you ready for that?”

“I can handle it,” I say, and an excited tremor passes through me, because I feel oddly sure about this. I think about how good it felt when Amy’s ankle was righting itself under my hand. Being a doctor would put me in contact with the people who need healing the most. I could help people. I could fix the broken things in this world.

I smile at Dr. Day, and she smiles back.

“This is what I want to do,” I tell her.

“All right, then,” she says. “Let’s get you started.”

Everybody takes the news that I’ve gone premed in a different way. Wan Chen, for instance, who’s premed herself, reacts like I’m suddenly competition. For a few days she doesn’t say more than two words to me, maneuvering around our tiny dorm room in chilled silence, until she realizes that we’re both in that insanely hard chemistry class and I’m pretty good at chemistry. Then she warms up to me fast. I hear her tell her mother on the phone in Mandarin that I’m a “nice girl, and very smart.” I make an effort not to smile when I hear her say it.

Angela instantly loves the idea of me as a doctor. “Very cool” are her exact words. “I believe we should use our gifts, you know, for good, not just sit on them unless we’re required to do some angel-related duty. If you can stomach all the blood and guts and gore—which I totally couldn’t, but kudos to you, if you can—then you should go for it.”

It’s Christian who doesn’t think it’s a good idea.

“A doctor,” he repeats when I tell him. “What brought this on?”

I explain about band run and Amy’s miraculously healed ankle and my subsequent aha moment. I expect him to be impressed. Excited for me. Approving. But he frowns.

“You don’t like it,” I observe. “Why?”

“It’s too risky.” He looks like he wants to say something else, but we’re standing on the crowded sidewalk outside the Stanford Bookstore, where I’ve bumped into him while coming out with my armload of poetry collections for my humanities class and a giant ten-pound textbook entitled Chemistry: Science of Change, which is what prompted this conversation. You could get caught using glory, he says in my head.

Relax, I reply. It’s not like I’m going to go around healing people right this minute. I’m looking into it as a possible career path, that’s all. No big deal.

But it feels like a big deal. It feels like my life finally has a—for lack of a better word—purpose, one that isn’t all about being an angel-blood but makes use of the angel-blood part of me, too. It feels right.

He sighs.

I get it, he says. I want to help people, too. But we have to lie low, Clara. You’re lucky that this girl you healed didn’t see what you did. How would you have explained that? What would you do if she was going around campus telling everybody about your magical glowing hands?

I don’t have an answer for him. My chin lifts. But she didn’t notice. I’ll be careful. I would only use glory when I thought it was safe, and the other times, I’d use regular medical stuff. Which is why I want to become a doctor. I have the power to heal people, Christian. How can I not use it?

We stand there for a minute, locked in a silent argument about whether or not it’s worth the risk, until it becomes clear that neither of us is going to change our mind. “I have to go,” I say finally, trying not to pout. “I have a set of problems on quantum mechanics to work through, if you think that’s not too dangerous for me to tackle.”

“Clara …,” Christian starts. “I think it’s great that you found a direction to go in, but …” All it would take is one slip, he says. The wrong person seeing you, one time, and then they could figure out what you are, and they’d come after you.

I shake my head. I can’t spend my entire life being afraid of the black-winged bogeymen. I have to live my life, Christian. I won’t be stupid about glory, but I won’t sit around and wait for my visions to happen in order to do something with it.

At the word visions a new worry springs up inside him, and I remember that there was something he promised to tell me. But I don’t want to hear about it now. I want to sulk.

I shift my heavy load of books to the other arm. “I’ve got to run. I’ll catch you later.”

“Okay,” he says stiffly. “See you around.”

I don’t like the feeling that’s hanging like a dark cloud over me as I walk back to my dorm.

That it doesn’t matter what I said about not wanting to be afraid. That I’m always, in some form or another, running away from something.

3

WHITE PICKET FENCE

This time someone else is with me in the blackness, another person’s breathing shuddering in and out somewhere behind me.

I still can’t see anything, can’t determine where I am, even though this is like the umpteenth time I’ve had the vision. It’s dark, as always. I am trying to keep quiet, trying not to move—not to breathe, even—so I can’t exactly explore my surroundings. The floor is slanted down. Carpeted. There’s the faint scent of sawdust in the air, new paint, and this: the hint of some distinctly masculine smell, like deodorant or aftershave, and now the breathing. Close, I think. If I turned and reached out, I could touch him.

There are footsteps above us: heavy and echoing, like people descending a set of wooden stairs. My body tenses. We’ll be found. Somehow I know this. I’ve seen it a hundred times in my visions. I’m seeing it right now. I want to get it over with, want to call the glory, but I don’t, on the off chance that it won’t happen this time. I still have hope.

There’s a noise from behind me, strange and high-pitched, like maybe a cat yowl or a birdcall. I turn toward the sound.

There’s a moment of silence.

Then comes a burst of light, blinding me. I flinch away from it.

“Clara, get down!” yells a voice, and in that wild, scuffling moment I instantly know who’s with me—I’d recognize his voice anywhere—and I find myself vaulting forward, upward, because some part of me knows that now I have to run.

I wake to a ray of sunshine on my face. It takes

me a second to place where I am: dorm room, Roble Hall. Light pouring through the window. The bells of Memorial Church in the distance. The smell of laundry detergent and pencil shavings. I’ve been at Stanford for more than a week now, and this room still doesn’t feel like home.

My sheets are tangled up in my legs. I must have really been trying to run. I lie there for a minute taking deep breaths from the abdomen, trying to calm my racing heart.

Christian’s there. In the vision. With me.

Of course Christian’s there, I think, still peeved with him. He’s been in every other vision I’ve had, so why stop now?

But there’s some kind of comfort in that.

I sit up and glance over at Wan Chen, who’s asleep in the bed on the other side of the room, snoring in little puffs. I free myself from the sheets and pull on some jeans and a hoodie, fight my hair into a ponytail, trying to keep quiet so I don’t wake her.

When I get outside there’s a large bird sitting on a lamppost near the dorm, a dark shape against the dawn-gray sky. It swivels to look at me. I stop.

I’ve always had a complicated relationship with birds. Even before I knew I was an angel-blood, I understood that there was something off about the way birds went quiet whenever I passed by, the way they followed me and sometimes, if I was oh-so-lucky, dive-bombed me, not in an unfriendly way, really, but in an I-want-to-see-you-closer sort of way. One of the hazards of having wings and feathers yourself, I suppose, even if they’re hidden most of the time: you attract the attention of other creatures with wings.

One time when I was having a picnic in the woods with Tucker, we looked up and our table was surrounded by birds—not just the common camp-robber jays that try to get the food you’re eating, but larks, swallows, wrens, even some kind of nuthatch Tucker said was extremely rare, all hanging out in the trees around our table.

“You’re like a Disney cartoon, Carrots,” Tucker teased me. “You should get them to make you a dress or something.”

But this bird feels different, somehow. It’s a crow, I think: jet-black, with a sharp, slightly hooked beak, perched on top of the post like a scene straight from Edgar Allan Poe. Watching me. Silent. Thoughtful. Deliberate.

Billy said once that Black Wings could turn into birds. That’s the only way they can fly; otherwise their sorrow weighs them down. So is this bird an ordinary crow?

I squint up at it. It cocks its head at me and stares right back with unblinking yellow eyes.

Dread, like a trickle of ice water, makes its way down my spine.

Come on, Clara, I think. It’s only a bird.

I scoff at myself and walk quickly past it, hugging my arms to my chest in the cold morning air. The bird squawks, a sharp, jarring warning that sends prickles to the back of my scalp. I keep walking. After a few steps I peer back over my shoulder at the lamppost.

The bird is gone.

I sigh. I tell myself that I’m being paranoid, that I’m just creeped out because of the vision. I try to put the bird out of my mind, and start walking again. Fast. Before I know it, I’m across campus, standing under Christian’s window, pacing back and forth on the sidewalk because I don’t actually know what I’m doing here.

I should have told him about the vision before, but I was too upset that he rejected my being-a-doctor idea. I should have told him before that, even. We’ve been here for almost two weeks, and neither one of us has talked about visions or purpose or any of the other angel-related stuff. We’ve been playing at being college freshmen, pretending that there’s nothing on our plates but learning people’s names and figuring out which rooms our classes are held in and trying not to look like complete morons at this school where everybody seems like a genius.

But I have to tell him now. I need to. Only it’s—I check my phone—seven fifteen in the morning. Too early for the guess-what-you’re-in-my-vision conversation.

Clara? His voice in my head is bleary.

Oh crap, sorry. I didn’t mean to wake you.

Where are you?

Outside. I—Here … I dial his number.

He answers on the first ring. “What’s up? Are you okay?”

“Do you want to hang out?” I ask. “I know it’s early….”

I can actually hear him smiling at the other end of the line. “Absolutely. Let’s hang out.”

“Oh, good.”

“But first let me put some pants on.”

“You do that,” I say, glad he can’t see me totally blushing at the idea of him in boxers. “I’ll be right here.”

He emerges a few minutes later in jeans and a brand-new Stanford sweatshirt, his hair rumpled. He restrains himself from hugging me. He’s relieved to see me after our argument at the bookstore a week ago. He wants to say he’s sorry. He wants to tell me that he’ll support me in whatever I decide to do.

He doesn’t have to say any of this out loud.

“Thanks,” I murmur. “That means a lot.”

“So what’s going on?” he asks.

It’s hard to know where to begin. “Do you want to get off campus for a while?”

“Sure,” he says, a spark of curiosity in his green eyes. “I don’t have class until eleven.”

I start walking back toward Roble. “Come on,” I call over my shoulder. He jogs to catch up with me. “Let’s take a drive.”

Twenty minutes later we’re cruising around Mountain View, my old hometown.

“Mercy Street,” Christian reads as we pass through downtown looking for this doughnut shop I used to go to where the maple bars are so good it makes you want to cry. “Church Street. Hope Street. I’m sensing a theme here….”

“They’re just names, Christian. I think someone had a laugh putting city hall on Castro between Church and Mercy. That’s all.” I check my mirrors and find myself unprepared for the glimpse of his gold-flecked eyes gazing at me steadily.

I glance away.

I don’t know what he expects of me now that I am officially single. I don’t know what I expect of myself. I don’t know what I’m doing.

“I’m not expecting anything, Clara,” he says, not looking at me. “If you want to hang with me, great. If you want some space, I get that too.”

I’m relieved. We can take this “we belong together” thing slow, figure out what that really means. We don’t have to rush. We can be friends.

“Thanks,” I say. “And look, I wouldn’t have asked you to hang out with me if I didn’t want to hang out with you.” You’re my best friend, I want to say, but for some reason I don’t.

He smiles. “Take me to your house,” he says impulsively. “I want to see where you lived.”

Awkward conversation officially over. Obediently I make a right toward my old neighborhood. But it’s not my house. Not anymore. It’s somebody else’s house now, and the thought makes me sad: someone else sleeping in my room, someone else at the kitchen window where Mom always used to stand watching the hummingbirds flit from flower to flower in the backyard. But that’s life, I guess. That’s being a grown-up. Leaving places. Moving on.

The sun is coming up behind the rows of houses when we get to my street. Sprinklers cast nets of white mist into the air. I roll the window down and drive with my right hand, let my left hand drag through the cool air outside. It smells so good here, like wet cement and fresh-cut grass, the aroma of bacon and pancakes wafting between the homes, garden roses and magnolia trees, the smells of my life before. It’s surreal, passing along these familiar tree-lined streets, seeing the same cars parked in the driveways, the same people headed off to work, the same kids walking to school, only a little bigger than the last time I saw them. It’s like time has stopped here, and these past two years and all the crazy stuff that went down in Wyoming never took place.

I park the car across the street from my old house.

“Nice,” Christian says, gazing out the open window at the big green two-story with blue shutters that was my home-sweet-home for the first sixteen years of my li

fe. “White picket fence and everything.”

“Yeah, my mom was a traditionalist.”

The house, too, looks exactly the same. I can’t stop staring at the basketball hoop that’s set up over the garage. I can almost hear Jeffrey practicing, the cadence of the ball hitting the cement, his feet shuffling, his exhaled breath as he jumps and puts the ball through the hoop, the way the backboard thumps and the net swishes, and Jeffrey hissing, “Nice,” between his teeth. How many times did I do my homework with that sound in the background?

“He’ll turn up,” Christian says.

I turn to look at him. “He’s sixteen, Christian. He should be home. He should have someone taking care of him.”

“Jeffrey’s strong. He can handle himself. You really want him to come home and get arrested and all that?”

“No,” I admit. “I’m just … worried.”

“You’re a good sister,” he says.

I scoff. “I messed everything up for him.”

“You love him. You would have helped him if you’d known what he was going through.”

I don’t meet his eyes. “How do you know? Maybe I would have blown him off and kept on obsessing about my own thing. I’m good at that.”

Christian catches his breath, then says more firmly, “It’s not your fault, Clara.”

I wish I believed him.

Silence falls over us again, but this time it’s weightier.

I should tell him about the vision. I should stop stalling. I don’t even know why I’m stalling.

“So tell me,” he says, leaning his elbow on the edge of the window.

Thus I rattle off every detail I can remember, ending with my revelation that it’s him there with me, him in the dark room. Him yelling for me to get down.

He’s quiet for a while after I’m done. “Well. It’s not a very visual type of vision, is it?”

“No, it’s pretty much darkness and adrenaline, at this point. What do you think?”

He shakes his head, baffled. “What does Angela say?”

I shift uncomfortably. “We haven’t really talked about it.”

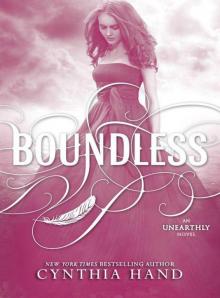

Boundless

Boundless My Plain Jane

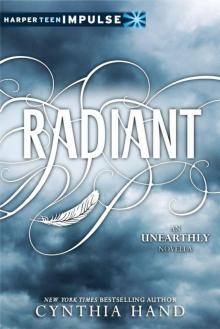

My Plain Jane Radiant

Radiant Hallowed

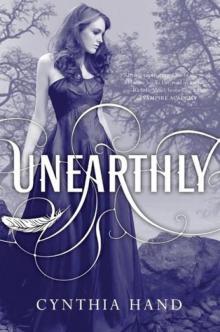

Hallowed 01 Unearthly

01 Unearthly My Lady Jane

My Lady Jane My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Unearthly

Unearthly The Last Time We Say Goodbye

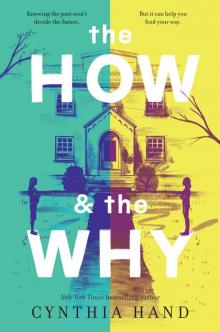

The Last Time We Say Goodbye The How & the Why

The How & the Why Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse)

Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse) Unearthly u-1

Unearthly u-1 Boundless (Unearthly)

Boundless (Unearthly) My Calamity Jane

My Calamity Jane Hallowed u-2

Hallowed u-2 Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel

Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel