- Home

- Cynthia Hand

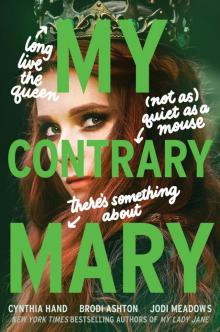

My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Read online

Dedication

For the people who feel like they have to be perfect.

And for France: we’re sorry for what we’re about to do to your history, but it was your turn.

Epigraph

The present time, together with the past, shall be judged by a great jovialist.

—Nostradamus

In my end is my beginning.

—Mary, Queen of Scots

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Books by the Authors

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

You may think you know the story.

All right, all right. We know. We just had to get it out of the way.

But now that we have your attention, we’d like to remind you that you actually have heard of this particular Mary. Does “Queen of Scots” ring a bell? If you’re a history buff (or if you watch TV), you probably know that this Mary was married (to a prince! Aw!), but she didn’t get to live happily ever after, because her beloved died young (of an ear infection! Boo!). After that, Mary bounced around from place to place (and husband to husband) simply trying to stay alive. But she posed a threat to another famous queen—Elizabeth I of England—and eventually the politics of the day caught up with Mary, and (gulp!) she lost her head.

It wasn’t the happiest of endings.

But you know us—we’re never satisfied until we’ve fixed the tragedies of history (which means changing things around a bit from what you’d read in the history books, like *cough* dates, names, and a few major details). So boy, have we got a story for you about Mary, Queen of Scots.

In those days (think 1560), the world was sharply divided between two groups of people: E∂ians and Verities. The E∂ians believed that inside every person was an animal—a creature you could become whenever you wished. One E∂ian could become a dog, for instance, and another could transform himself into a horse (call him G). The other faction—the Verities—was not amused by these shape-shifting shenanigans. They believed that people should be people, period.

The friction between these two groups led to a lot of conflict. Like, a lot. Wars were fought. People on both sides were thrown into prison and tortured. And more than one person lost her head.

Which brings us back to our story, starring a teenage queen who hates being told what to do, a prince who has never felt particularly charming, and the daughter of a famous seer who’s about to be dragged into a political game of cat and mouse.

One thing’s for certain: it’s not easy being queen.

ONE

Mary

Imagine, if you will, dear reader, the Louvre in Paris, France, in the days before it became a museum: an enormous marble palace stretching along the banks of the Seine. Then imagine a garden behind that palace, a large expanse of meticulously upkept greenery, fountains, and courtyards. In the back of one such courtyard was a . . . butt. No, dear reader, not a backside-type butt, but an archery butt, which is the thingy with the bull’s-eye on it that archers shoot arrows at. And roughly fifteen paces from the butt, there stood a girl.

But this girl was not just a girl. She was a queen.

Not a princess. Not a lady.

A queen.

Her name was Mary.

At the moment, Mary was concentrating on the butt.

She lifted the bow in her arms, drew it back, and aimed. One brown eye squeezed shut, while the other focused sharply on the bull’s-eye. She blew out a slow breath, then loosed the arrow.

It flew fast and true, striking the butt with a solid thwap.

The four ladies-in-waiting standing around her all clapped enthusiastically.

“Well done, Your Majesty,” exclaimed one.

“You’re getting better,” said another.

“You were always quite good, I thought,” said a third.

The fourth one was not much of a talker, but she smiled approvingly.

The queen strode over to inspect the butt herself. It had been a very good shot, hitting nearly, but not quite, the exact center of the bull’s-eye. She’d been about a thumb’s width off.

“I’ll try again,” she said resolutely, and marched back for yet another attempt. One would have thought she intended to murder that poor defenseless butt by the way she narrowed her eyes and scowled it down.

Thwap.

This time she was a pinkie’s width off.

Mary resisted the urge to stamp her foot, because queens do not stamp.

“One more time,” she said tersely.

One of her ladies-in-waiting sighed. “Again? We’ve been out here for ages. It’s time for lunch.”

(Some helpful backstory: Mary had come to live in France when she was only five years old, to be the fiancée of the dauphin—aka the prince—while her mother ruled Scotland on her behalf. To this new life, Mary had brought along her four best friends—think the world’s longest sleepover—every single one of whom also happened to be named Mary: Mary Fleming, Mary Seton, Mary Beaton, and Mary Livingston. The girls all had nicknames, to avoid confusion, but collectively they were known as “the Four Marys.” The particular Mary who’d just complained was Mary Fleming, whom everyone called Flem, for short. Flem was the one of the four who was most ruled by the dictates of her stomach.)

Speaking of stomachs, the queen realized she was a bit hungry. She’d only nibbled at breakfast.

“It’s getting rather hot,” said another Mary, this one Mary Livingston, also known as Liv.

All of a sudden Mary noticed that she was feeling overheated. The combination of the morning’s exertion and her heavy green velvet gown was causing her to sweat—oh, we mean glow, of course, since queens do not sweat.

“A shipment of lemons and oranges arrived from Spain yesterday,” noted Mary Beaton—nicknamed Bea. “Perhaps there’s lemonade.”

Mary did love lemonade.

The fourth lady, whom everyone called Hush, said nothing but appeared a bit parched and wilted and looked hopeful at the prospect of going inside.

“One more time,” Mary said.

But really she meant however many times it took until she got it perfect.

The next shot was an entire hand’s width from the bull’s-eye. Mary’s foot did a little shuffle forward that was definitely not a stamp. She twisted her amethyst ring around on her finger—a habit she had

whenever something displeased or troubled her.

“Oh, look,” Bea said suddenly. “Here come your uncles.”

Mary turned, and yes, strolling in her direction across the courtyard were Francis de Guise and Charles de Lorraine.

She handed the bow off to Liv as everyone all did the appropriate bowing and curtsying.

“Ah, my dear,” said Uncle Charles, taking her hands and drawing her in to kiss her cheeks, his beard scratchy against her face. “How lovely you look. Did you know that the writer Jean de Beaugue recently described you as ‘one of the most perfect creatures that ever was seen’?”

“Yes, you’re always so exquisite,” added Uncle Francis (kiss, kiss). “And only yesterday I read what Jacques de Lorges wrote about you as being ‘so charming and intelligent as to give everyone who sees her incomparable joy and satisfaction.’ I was so very proud.”

(We, as your narrators, think this is a little much, but we get it: Mary was undeniably beautiful, with dark auburn hair that fell nearly to her waist, a fine complexion, and rich, expressive brown eyes. There was just something about Mary: a regal bearing, a grace and confidence that seemed well beyond her seventeen years. But to us, it seems like a lot of pressure.)

“Thank you,” Mary said humbly, because the best queens are humble.

Uncle Charles looked at the butt. “Are you still playing at archery? I’d have thought you would have given that up by now.”

Mary’s chin lifted. “I quite enjoy archery, I find.”

Uncle Francis went over and examined the butt. “Not quite hitting the bull’s-eye, though, are you?”

“I will,” Mary said steadily.

Uncle Charles smiled. “No doubt, my dear. You keep trying.”

“You’ve got to hold the bow steady,” advised Uncle Francis.

“Yes, I—”

“And stand up very straight, and have you tried closing one eye?”

“Yes, Uncle, I—”

“And you should exhale, right before you—”

“Yes, Uncle,” Mary said more firmly. “I know.”

Her uncles were the only people Mary knew who dared to interrupt her, but she allowed it. These two men were, in essence, her guardians. She knew they only cared for her welfare, even if they could be a bit overbearing at times. They were family.

“I’m so pleased to see you,” she said warmly. “But is there a particular reason you’ve come to visit me?” When she’d been younger they’d done monthly inspections of her rooms, her clothing, her companions and tutors, to make sure she was being brought up properly, but that had stopped more than a year ago. She liked to think that was because now they trusted her to use her own judgment of such things.

Uncle Charles looked grave. “We’ve had a letter from your mother.”

“She wrote to you?” Mary glanced quizzically at her lady Bea, who handled all of Mary’s correspondence with her mother. She’d received no recent letters. “What did she say?”

Uncles Charles reached into his doublet and pulled out a slightly damp fold of parchment bearing a royal seal on one side, and the handwriting of Mary’s mother on the other. He handed Mary the letter.

She took it and unfolded it right away, walking off a few paces while she read quickly. “She says there’s trouble.” Her brow furrowed. “Some malcontent named John Knox stirring up problems.”

“He’s a filthy E∂ian,” Uncle Charles muttered. Uncle Charles was a religious man, a cardinal in the Verity Church, which meant that he wore the red robes and the oblong red pointy hat, and also that, more than anything, he hated E∂ians.

“He means to instigate a full-out rebellion against your mother,” added Uncle Francis.

“Yes,” Mary murmured, continuing to read. “He claims that she is not the rightful monarch of Scotland.”

“No, he claims that you are not the rightful monarch of Scotland, being a woman,” said Uncle Francis. “And your mother, as regent, is even more of an abomination in his eyes.”

“He seeks to overthrow the power of the Verity Church in Scotland.” Uncle Charles looked grim. “Starting with you.”

“But—” This was just so frustrating, considering. “What’s to be done about it? He won’t succeed, will he? Is Mother in danger? Perhaps I should—”

Uncle Charles took her hand and patted it. “We’ll take care of it, my dear. We always do.”

Mary nodded. They always did.

“Yes,” said Uncle Francis almost gleefully. He was a military man, a general who had led many a battle in his time, and he relished any chance to use his strategical prowess. “We can handle Scotland.”

Mary was grateful for her uncles, even though she knew they could be a bit wicked in the pursuit of their goals. They were wicked, she knew, on her behalf. She probably would have lost her crown a hundred times by now if her de Guise relatives hadn’t been there to intervene for her. Still, it went against her better judgment, letting others take care of what Scotland needed. Part of Mary always felt that she should go back there and take care of it herself.

Otherwise it was like she was a queen in name only.

She twisted her amethyst ring.

“Now, don’t worry your pretty head about all of this dreary political nonsense,” said Uncle Charles. “Why don’t you come inside and read to us for a while? I simply love to hear the dulcet tones of your sweet voice.”

“Thank you, Uncle,” Mary said, er, sweetly. “But I’d like to stay out here and continue my practice.”

Both uncles frowned.

“But it’s so hot out,” said Uncle Francis.

“And it’s almost lunchtime,” Uncle Charles said.

“That’s right!” exclaimed Flem, and the other Marys murmured their agreement.

“Nevertheless,” said Mary. “I will stay.”

“Very well,” said Uncle Francis finally. “You should join us for supper, then. We’re dining with the king tonight.”

Mary inwardly groaned. She’d been looking forward to a quiet evening in with her ladies, doing embroidery by the fire, perhaps some knitting or shoe design if things got crazy. The last thing she wanted was to be stuck at a stuffy dinner with her uncles and the king. Of course, Francis (her fiancé Francis, we mean) would undoubtedly be there too, which would make it all more bearable, as the two of them always came up with amusing things to do to pass the time.

“You must come,” Uncle Francis said. “We insist.”

All four of the Four Marys caught their breaths.

Mary smiled tightly. She never did like to be told she must anything.

“I’ll consider it,” she said softly.

After her uncles retreated into the palace, Mary picked up her bow once more. She swept her hair over one shoulder, adjusted her stance, drew, and let loose.

The arrow struck the bull’s-eye hard, burying itself deep into the straw at the exact center.

Mary handed the bow to Liv.

“Now can we have lunch?” asked Flem in relief.

“Yes.”

They moved toward the palace, the Four Marys flanking her on every side.

Mary was frowning.

“You’re worried about your mother,” Liv said.

“Of course.” She was always worried about her mother these days. Things were heating up between the E∂ians and the Verities everywhere, but especially, it seemed, in Scotland.

“Would you like to draft a letter for me to take to her?” asked Bea.

“Yes. Not tonight, though,” Mary said. “I want some time to think about what I should say.”

“Do we really have to go to dinner with the king?” whispered Hush.

“The food will be good,” said Flem cheerfully. That was true. The king did like to eat.

“Yes, but the king and the uncles together are quite insufferable,” said Mary. “They can’t seem to stop congratulating themselves on being the masters of the universe.”

“But they insisted that you attend,” said Bea.

Mary’s lips pursed. “They can insist as much as they like. I am not theirs to order about. I am the queen of Scotland.”

Sometimes it was good to be queen.

“We could use a girls’ night out,” Liv said lightly.

All five Marys stopped and looked at each other.

“Oh, let’s!” Flem clapped her hands.

“You mean a boys’ night out,” said Bea, tucking a strand of her black hair behind her ear and smiling slyly.

“It’s been ages,” said Liv.

“I like the music,” murmured Hush.

Mary smiled. A night on the town sounded like just the remedy to her worries. “All right,” she agreed. “Let’s.”

“I want to be the one to wear the false mustache!” Flem exclaimed a few hours later, as the queen and the Four Marys put the finishing touches on their disguises.

“You got to wear it last time,” argued Bea.

“I don’t want to wear it,” said Hush softly. “It itches.”

It was decided that Flem would wear it, because she really, really wanted to, and besides, she looked so funny wearing a mustache that they all couldn’t help but giggle at the sight. Flem was the shortest and stoutest of the ladies, with curly chestnut-colored hair and wide brown eyes.

“Well, gentlemen,” Mary said as they donned their feathered hats. “We make a fine company of men.”

Liv had been right—it felt like ages since they’d played this game, in which they dressed up as boys and sneaked into the city to their favorite tavern. They always had a merry time chatting with the townsfolk, drinking ale, and dancing to the lively music, a much better time in general than they did at the palace’s most lavish parties.

And even though Mary’s bosom was wrapped up tight in layers of cloth to flatten her curves, as they helped each other climb over the garden wall, she felt like she could finally breathe.

Tonight, she’d push her worries for Scotland and her mother from her mind.

And for just a few hours, she’d forget she was a queen.

TWO

Ari

Nostradamus was losing his touch. In the past hour the world’s most famous seer and revelator had started to refer to his own daughter as “Galileo” instead of her given name, Aristotle—or Ari, as she liked to be called. Then he’d broken her best glass vial trying to brew a remedy for unrequited love. (Ari wouldn’t have minded if that one had worked.) But when he predicted that France was soon going to be ruled by a frog, she decided she needed to get out of the palace for a while.

Boundless

Boundless My Plain Jane

My Plain Jane Radiant

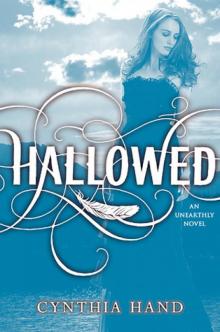

Radiant Hallowed

Hallowed 01 Unearthly

01 Unearthly My Lady Jane

My Lady Jane My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Unearthly

Unearthly The Last Time We Say Goodbye

The Last Time We Say Goodbye The How & the Why

The How & the Why Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse)

Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse) Unearthly u-1

Unearthly u-1 Boundless (Unearthly)

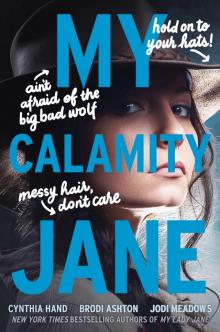

Boundless (Unearthly) My Calamity Jane

My Calamity Jane Hallowed u-2

Hallowed u-2 Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel

Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel