- Home

- Cynthia Hand

The Last Time We Say Goodbye

The Last Time We Say Goodbye Read online

Dedication

FOR JEFF.

Because this is the only way I know to reach for you.

Epigraph

Help your brother’s boat across,

and your own will reach the shore.

—HINDU PROVERB

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

5 February Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

9 February Chapter 4

Chapter 5

12 February Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

14 February Chapter 9

Chapter 10

16 February Chapter 11

Chapter 12

17 February Chapter 13

Chapter 14

21 February

22 February

23 February Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

5 March Chapter 18

Chapter 19

9 March Chapter 20

Chapter 21

11 March Chapter 22

Chapter 23

13 March Chapter 24

Chapter 25

15 March Chapter 26

17 March Chapter 27

Chapter 28

20 March Chapter 29

22 March Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

30 March Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

31 March Chapter 36

Chapter 37

From the Author

Back Ads

About the Author

Books by Cynthia Hand

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

5 February

First I’d like to state for the record that the whole notion of writing this down was not my idea. It was Dave’s. My therapist’s. He thinks I’m having trouble expressing my feelings, which is why he suggested I write in a journal—to get it out, he said, like in the old days when physicians used to bleed their patients in order to drain the mysterious poisons. Which almost always ended up killing them in spite of the doctors’ good intentions, I might point out.

Our conversation went something like this:

He wanted me to start taking antidepressants.

I told him to stick it where the sun don’t shine.

So we were at a bit of an impasse.

“Let’s take a new approach,” he said finally, and reached behind him and produced a small black book. He held it out to me. I took it, thumbed it open, then looked up at him, confused.

The book was blank.

“I thought you might try writing, as an alternative,” he said.

“That’s a moleskin notebook,” he elaborated when all I did was stare at him. “Hemingway used to write in those.”

“An alternative to what?” I asked. “To Xanax?”

“I want you to try it for a week,” he said. “Writing, I mean.”

I tried to hand the journal back to him. “I’m not a writer.”

“I’ve found that you can be quite eloquent, Alexis, when you choose to be.”

“Why? What’s the point?”

“You need an outlet,” he said. “You’re keeping everything inside, and it’s not good for you.”

Nice, I thought. Next he’d be telling me to eat my vegetables and take my vitamins and be sure to get 8 uninterrupted hours of sleep every night.

“Right. And you would be reading it?” I asked, because there’s not even a remote possibility that I’m going to be doing that. Talking about my unexpectedly tragic life for an hour every week is bad enough. No way I’m going to pour my thoughts out into a book so that he can take it home and scrutinize my grammar.

“No,” Dave answered. “But hopefully you might feel comfortable enough someday to talk with me about what you’ve written.”

Not likely, I thought, but what I said was, “Okay. But don’t expect Hemingway.”

I don’t know why I agreed to it. I try to be a good little patient, I guess.

Dave looked supremely pleased with himself. “I don’t want you to be Hemingway. Hemingway was an ass. I want you to write whatever strikes you. Your daily life. Your thoughts. Your feelings.”

I don’t have feelings, I wanted to tell him, but instead I nodded, because he seemed so expectant, like the status of my mental health entirely depended on my cooperation with writing in the stupid journal.

But then he said, “And I think for this to be truly effective, you should also write about Tyler.”

Which made all the muscles in my jaw involuntarily tighten.

“I can’t,” I managed to get out from between my teeth.

“Don’t write about the end,” Dave said. “Try to write about a time when he was happy. When you were happy, together.”

I shook my head. “I can’t remember.” And this is true. Even after almost 7 weeks, a mere 47 days of not interacting with my brother every day, not hurling peas at him across the kitchen table, not seeing him in the halls at school and acting, as any dutiful older sister would, for the sake of appearances, like he bugged me, Ty’s image has grown hazy in my mind. I can’t visualize the Ty that isn’t dead. My brain gravitates toward the end. The body. The coffin. The grave.

I can’t even begin to pull up happy.

“Focus on the firsts and the lasts,” Dave instructed. “It will help you remember. For example: About twenty years ago I owned an ’83 Mustang. I put a lot of work into that car, and I loved it more than I should probably admit, but now, all these years later, I can’t fully picture it. But if I think about the firsts and the lasts with the Mustang, I could tell you about the first time I drove it, or the last time I took it on a long road trip, or the first time I spent an hour in the backseat with the woman who would become my wife, and then I see it so clearly.” He cleared his throat. “It’s those key moments that burn bright in our minds.”

This is not a car, I thought. This is my brother.

Plus I thought Dave might have just been telling me about having sex with his wife. Which was the last thing I wanted to picture.

“So that’s your official assignment,” he said, sitting back as if that settled it. “Write about the last time you remember Tyler being happy.”

Which brings me to now.

Writing in a journal about how I don’t want to be writing in a journal.

I’m aware of the irony.

Seriously, though, I’m not a writer. I got a 720 on the writing section of the SAT, which is decent enough, but nobody ever pays any attention to that score next to my perfect 800 in math. I’ve never kept a diary. Dad got me one for my 13th birthday, a pink one with a horse on it. It ended up on the back of my bookshelf with a copy of the NIV Teen Study Bible and the Seventeen Ultimate Guide to Beauty and all the other stuff that was supposed to prepare me for life from ages 13 to 19—as if I could ever be prepared for that. Which is all still there, 5 years later, gathering dust.

That’s not me. I was born with numbers on the brain. I think in equations. What I would do, if I could really put this pen to paper and produce something useful, is take my memories, these fleeting, painful moments of my life, and find some way to add and subtract and divide them, insert variables and move them, try to isolate them, to discover their elusive meanings, to translate them from possibilities to certainties.

I would try to solve myself. Find out where it all went wrong. How I got here, from A to B, A being the Alexis Riggs who was so sure of herself, who was smart and solid and laughed a lot and cried occasionally and didn’t fail at the most important things.

To this.

But instead, th

e blank page yawns at me. The pen feels unnatural in my hand. It’s so much weightier than pencil. Permanent. There are no erasers, in life.

I would cross out everything and start again.

1.

MOM IS CRYING AGAIN THIS MORNING. She does this thing lately where it’s like a faucet gets turned on inside her at random times. We’ll be grocery shopping or driving or watching TV, and I’ll glance over and she’ll be silently weeping, like she’s not even aware she’s doing it—no sobbing or wailing or sniffling, just a river of tears flowing down her face.

So. This morning. Mom cooks breakfast, just like she’s done nearly every single morning of my life. She scrapes the scrambled eggs onto my plate, butters the toast, pours me a glass of orange juice, and sets it all on the kitchen table.

Crying the entire time.

When she does the waterworks thing, I try to act like nothing is out of the ordinary, like it’s perfectly normal for your mother to be weeping over your breakfast. Like it doesn’t get to me. So I say something chipper like, “This looks great, Mom. I’m starved,” and start pushing the burned food around my plate in a way that I hope will convince her I’m eating.

If this was before, if Ty were here, he’d make her laugh. He’d blow bubbles in his chocolate milk. He’d make a face out of his bacon and eggs, and pretend to talk with it, and scream like he was in the middle of a slasher film as he slowly ate one of the eyes.

Ty knew how to fix things. I don’t.

Mom sits down across from me, tears dripping off her chin, and folds her hands in her lap. I stop fake-eating and bow my head, because even though I quit believing in God awhile ago, I don’t want to complicate things by confessing my budding atheism to my mother. Not now. She has enough to deal with.

But instead of praying she wipes her wet face with her napkin and looks up at me with shining eyes, her eyelashes stuck damply together. She takes a deep breath, the kind of breath you take when you’re about to say something important. And she smiles.

I can’t remember the last time I saw her smile.

“Mom?” I say. “Are you okay?”

And that’s when she says it. The crazy thing. The thing I don’t know how to handle.

She says:

“I think your brother is still in the house.”

She goes on to explain that last night she woke from a dead sleep for no reason. She got up for a glass of wine and a Valium. To help her get back to sleep, she says. She was standing at the kitchen sink when, out of the blue, she smelled my brother’s cologne. All around her, she says.

Like he was standing next to her, she says.

It’s distinctive, that cologne. Ty purchased it for himself two Christmases ago in like a half-gallon bottle from Walmart, this giant radioactive-sludge-green container of Brut—“the essence of man,” the box had bragged. Whenever my brother wore that stuff, which was pretty often, that smell would fill the room. It was like a cloud floating six feet ahead of him as he walked down the hall at school. And it’s not that it smelled bad, exactly, but it forced you into this weird takeover of the senses. SMELL ME, it demanded. Don’t I smell manly? HERE I COME.

I swallow a bite of eggs and try to think of something helpful to say.

“I’m pretty sure that bottle gives off some kind of spontaneous emissions,” I tell her finally. “And the house is drafty.”

There you go, Mom. Perfectly logical explanation.

“No, Lexie,” she says, shaking her head, the remains of the strange smile still lingering at the corners of her mouth. “He’s here. I can feel it.”

The thing is, she doesn’t look crazy. She looks hopeful. Like the past seven weeks have all been a bad dream. Like she hasn’t lost him. Like he isn’t dead.

This is going to be a problem, I think.

2.

I RIDE THE BUS TO SCHOOL. I know it’s a bold statement to make as a senior, especially one who owns a car, but in the age-old paradox of choosing between time and money, I’ll choose money every time. I live in the sleepy little town of Raymond, Nebraska (population 179), but I attend school in the sprawling metropolis of Lincoln (population 258,379). The high school is 12.4 miles away from my house. That’s 24.8 miles round trip. My crappy old Kia Rio (which I not-so-affectionately refer to as “the Lemon”) gets approximately 29 miles to the gallon, and gas in this neck of Nebraska costs an average of $3.59 per gallon. So driving to school would cost me $3.07 a day. There are 179 days of school this year, which adds up to a whopping $549.53, all so I can have an extra 58 minutes of my day.

It’s a no-brainer. I have college to pay for next year. I have serious savings, a plan. Part of that plan involves taking the school bus.

I actually liked the bus. Before, I mean. When I used to be able to put in my earbuds and crank up the Bach and watch the sun come up over the white, empty cornfields and the clichéd sun-beaten farmhouses tucked back from the road. The windmills outside turning. Cows huddling together for warmth. Birds—gray-slated junco and chickadees and the occasional bright flashes of cardinals—slipping effortlessly through the winter air. It was quiet and cozy and nice.

But since Ty died, I feel like everybody on the bus is watching me, some people out of sympathy, sure, ready to rush over with a tissue at a moment’s notice, but others like I’ve become something dangerous. Like I have the bad gene in my blood, like my sad life is something that could be transmitted through casual contact. Like a disease.

Yeah, well, screw them.

Of course, being angry is pointless. Unproductive. They don’t understand yet. That they are all waiting for that one phone call that will change everything. That every one of them will feel like me eventually. Because someone they love will die. It’s one of life’s cruel certainties.

So with that in mind I try to ignore them, turn up my music, and read. And I don’t look up until we’ve gone the twelve miles to school.

This week I’m rereading A Beautiful Mind, which is a biography of the mathematician John Nash. There was a movie, which had entirely too little math, in my opinion, but was otherwise okay. The book is great stuff. I like thinking about how Nash saw our behavior as mathematical. That was his genius, even if he did go crazy and start to see imaginary people: he understood the connections between numbers and the physical world, between our actions and the invisible equations that govern them.

Take my mother, for instance, and her announcement that my brother is still with us. She’s trying to restructure our universe so that Ty doesn’t disappear. Like the way a fish will thrash its body on the sand when it’s beached, an involuntary reaction, a survival mechanism, in hopes that it might rock its way back into the water.

Mom is trying to find her way back to the water. It makes sense, if I look at it from that angle.

Not that it’s healthy. Not that I know what to do about it.

I don’t for a second believe that Ty is still in our house. He’s gone. The minute the life left him, the minute the neurons in his brain quit firing, he stopped being my brother. He became a collection of dead cells. And is now, thanks to the miracles of the modern embalming process, well on his way to becoming a coffin full of green goo.

I will never see him again.

The thought brings back the hole in my chest. This keeps happening, every few days since the funeral. It feels like a giant gaping cavity opens up between my third and fourth ribs on the left side, an empty space that reveals the vinyl bus seat behind my shoulder blades. It hurts, and my whole body tightens with the pain, my jaw locking and my fists clenching and my breath freezing in my lungs. I always feel like I could die, when it happens. Like I am dying. Then, as suddenly as it comes on, the hole fills in again. I can breathe. I try to swallow, but my mouth has gone bone dry.

The hole is Ty, I think.

The hole is something like grief.

School is largely uneventful. I float through on autopilot, lost in thoughts of John Nash and beached fish and the logistics of how currents of air coul

d have carried the scent of my brother’s cologne from where it sits all dusty by the sink in the basement bathroom through the den, up the stairs, to the kitchen to utterly confuse my mother.

Then I hit what used to be the best class of the day: sixth period, Honors Calculus Lab. I like to call it Nerd Central, the highest concentration of the smartest people in the school you’ll ever be likely to find in a given place.

My home sweet home.

The point of this class is to give the students time to study and do their calculus homework. But because we are nerds, we all finish our homework in the first ten minutes of class. Then we spend the rest of the hour playing cards: poker, war, hearts, rummy, whatever strikes our fancy.

Our teacher, the brilliant and mathtastic Miss Mahoney, sits at her desk at the front of the room and pretends that we’re doing serious scholarly work. Because it’s kind of her free period, too, since the school budget cutbacks eliminated her prep hour.

She has a thing for cat videos on YouTube.

We’ve all got our weaknesses.

So there we are, playing a rousing game of five-card draw. I’m killing it. I have three aces. Which is a lovely math problem all on its own—the probability of getting three aces in one hand is 94/54,145 or (if you want to talk odds) 575 to 1, which is pretty freaking unlikely, when you think about it.

Jill is sitting on my left, twirling a lock of her bright red hair around her finger. I think she means the hair twirling to look like some kind of tell, as if she has an amazing hand, but it probably means just the opposite. Eleanor is sitting on my right, and she has a lousy hand, which I know because she just comes out and says, “I have a lousy hand,” and folds. That’s El—she says what she thinks, no filter.

Boundless

Boundless My Plain Jane

My Plain Jane Radiant

Radiant Hallowed

Hallowed 01 Unearthly

01 Unearthly My Lady Jane

My Lady Jane My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Unearthly

Unearthly The Last Time We Say Goodbye

The Last Time We Say Goodbye The How & the Why

The How & the Why Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse)

Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse) Unearthly u-1

Unearthly u-1 Boundless (Unearthly)

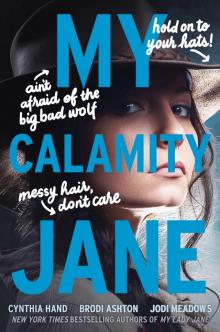

Boundless (Unearthly) My Calamity Jane

My Calamity Jane Hallowed u-2

Hallowed u-2 Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel

Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel