- Home

- Cynthia Hand

Boundless (Unearthly) Page 2

Boundless (Unearthly) Read online

Page 2

“Hey!” I object to her tone on the subject of blondes.

“And they’re complete fuzzies. One’s a communications major—whatever that means—and one is undecided.”

“There’s nothing wrong with being undecided.” I glance at Christian, a tad embarrassed about my undecidedness.

“I’m undecided,” he says. Angela and I stare at him, shocked. “What, I can’t be undecided?”

“I assumed you’d be a business major,” Angela says.

“Why?”

“Because you look really stellar in a suit and tie,” she says with false sweetness. “You’re pretty. You should play to your strengths.”

He refuses to rise to the bait. “Business is Walter’s thing. Not mine.”

“So what is your thing?” Angela asks.

“Like I said, I haven’t decided.” He gazes at me intently, the gold flecks in his green eyes catching the light, and I feel heat move into my cheeks.

“Where is Walter, anyway?” I ask to change the subject.

“With Billy.” He turns and points at the designated parent section of the quad, where, sure enough, Walter and Billy look like they’re deep in conversation.

“They’re a cute couple,” I say, watching Billy as she laughs and puts her hand on Walter’s arm. “Of course I was surprised when Billy called me this summer to tell me that she and Walter were getting married. I did not see that coming.”

“Wait, Billy and Walter are getting married?” Angela exclaims. “When?”

“They got married,” Christian clarifies. “July. At the meadow. It was pretty sudden.”

“I didn’t even know they liked each other,” I say before Angela can deliver the joke I know she’s cooking up about how Christian and I are now some kind of weird brother and sister, since his legal guardian has married my legal guardian.

“Oh, they like each other,” Christian says. “They’re trying to be discreet, for my sake, I guess. But Walter can’t stop thinking about her. Loudly. And in various states of undress, if you know what I mean.”

“Ugh. Don’t tell me. I’m going to have to scrub my brain with the little bit I saw in her head this week. Is there a bearskin rug at your house?”

“I think you just ruined my living room for me,” he says with a groan, but he doesn’t mean it. He’s happy about the Billy-Walter situation. He thinks it’s good for Walter. Keeps his mind off things.

What things? I ask.

Later, he says. I’ll tell you all about it. Later.

Angela lets out an exasperated sigh. “Oh my God, you guys. You are totally doing it again.”

After the orientation speeches, them telling us how proud we should be of ourselves, what high hopes they have for our futures, the amazing opportunities we’ll have while we’re at “the Farm,” as they call Stanford, we’re all supposed to head back to our dorms and get acquainted with one another.

This is the point when they tell the parents to go home.

Angela’s mom, Anna, who’s been her intensely quiet self, sitting in the backseat of my car reading her Bible for the entire thousand-mile trip, suddenly bursts into tears. Angela is mortified, red-cheeked as she escorts her sobbing mother out to the parking lot, but I think it’s nice. I wish my mom were here to cry over me.

Billy gives me another one of those encouraging shoulder squeezes. “Knock ’em dead, kid,” she says simply, and then she’s gone, too.

I pick a comfy sofa in the lounge and pretend to study the patterns on the carpet while the rest of the students are saying their own tearful good-byes. After a while a guy with short, dyed-blond hair comes in and sits across from me, sets a hefty stack of folders on the coffee table. He smiles, reaches out to shake my hand. “I’m Pierce.”

“Clara Gardner.”

He nods. “I think I’ve seen your name on a couple of lists. You’re in B wing, right?”

“Third floor.”

“I’m the fee here in Roble,” he says.

I stare at him blankly.

“P-H-E,” he explains. “It stands for peer health educator. Kind of like the doctor of the dorm. I’m where you go for a Band-Aid.”

“Oh, right.”

He’s looking at my face in a way that makes me wonder if I have food on it.

“What? Do I have the words clueless freshman tattooed across my forehead?” I ask.

He smiles, shakes his head. “You don’t look scared.”

“Excuse me?”

“Freshmen usually seem pretty terrified, first week on campus. They wander around like lost little puppies. Not you, though. You look like you’ve got things all under control.”

“Oh. Thanks,” I say. “But I hate to tell you, it’s an act. Inside I’m a nervous wreck.”

I’m not, actually. I guess next to fallen angels, funerals, and forest fires, Stanford feels like a pretty safe place. Everything’s familiar here: the California smells of exhaust and eucalyptus trees and carefully landscaped roses in the air, palm trees, the Caltrain noise in the distance, the same old varieties of plants that I grew up with outside the windows.

It’s the other stuff that scares me: the dark, windowless room in my vision, what’s going to happen in that place, the bad thing that’s happened before I end up hiding there. The possibility that this is going to be my entire life: one vague, terrifying vision after another, for the next hundred years. That’s what’s scary. That’s what I am trying very hard not to think about.

Pierce writes a five-digit number on a Post-it and holds it out. “Call me if you need anything. I’ll come running.”

He’s flirting, I think. I take the Post-it. “Okay.”

Just then Angela bustles in, running her hands down the sides of her leggings like she’s wiping off her mother’s emotions. She stops short when she sees Pierce.

She doesn’t look scared, either. She looks like she’s come to conquer.

“Zerbino, Angela,” she says matter-of-factly when Pierce opens his mouth to greet her. She glances at the folders on the table. “Have you got something in that pile with my name on it?”

“Yeah, sure,” he says, flustered, and rummages through the folders until he lands on Z and a packet for Angela. Then he fishes one out for me. He gets up. Checks his watch. “Well, nice to meet you, girls. Get comfortable. We’ll probably start our getting-to-know-you games in about five minutes.”

“What’s that?” Angela gestures to my Post-it as he walks away.

“Pierce.” I stare at his retreating back. “Anything I need, he’ll come running.”

She shoots a glance at him over her shoulder, smiles thoughtfully. “Oh, really? He’s cute.”

“I guess.”

“Right, I forgot. You only have eyes for Tucker still. Or is it Christian now? I can never keep track.”

“Hey. Like, ouch,” I say. “You’re being awfully rude today.”

Her expression softens. “Sorry. I’m tense. Change is hard for me, even the good changes.”

“For you? No way.”

She drops into the seat next to mine. “You seem relaxed, though.”

I stretch my arms over my head, yawn. “I’ve decided to stop stressing about everything. I’m going to start fresh. Look.” I dig around in my bag for the rumpled piece of paper and hold it up for her to read. “Behold, my tentative schedule.”

Her eyes quickly scan the page. “I see you took my advice and enrolled in that Intro to Humanities class with me. The Poet Re-making the World. You’ll like it, I promise,” she says. “Interpreting poetry’s easy, because you can make it mean pretty much whatever you want it to mean. It will be a cakewalk kind of class.”

I seriously doubt that.

“Hmm.” Angela frowns as she reads farther down. “Art history?” She quirks an eyebrow at me. “Science, Technology, and Contemporary Society? Intro to Film Studies? Modern Dance? This is kind of all over the place, C.”

“I like art,” I say defensively. “It’s simple for you, since you’re a histor

y major, so you take history classes. But I’m—”

“Undecided,” she provides.

“Right, and I didn’t know what to take, so Dr. Day told me to enroll in a bunch of different classes and then drop the ones I didn’t respond to. But look at this one.” I point to the last class on the list.

“Athletics 196,” she reads above my finger. “Practice of Happiness.”

“Happiness class.”

“You’re taking a class on happiness,” she says, like that has got to be the most total slacker class in the universe.

“My mom said I was going to be happy at Stanford,” I explain. “So that’s what I intend to be. I’m going to find my happiness.”

“Good for you. Take charge of yourself. It’s about freaking time.”

“I know,” I say, and I mean it. “I’m ready to stop saying good-bye to things. I’m going to start saying hello.”

2

BAND RUN

That night I wake up at two in the morning to somebody pounding on my door.

“Hello?” I call out warily. There’s a jumble of noise from outside, music and people shouting and frantic footsteps in the hall. Wan Chen and I both sit up, exchange worried glances, and then I slide out of bed to answer the door.

“Rise and shine, dear freshmen,” says Stacy, our RA, in a chipper voice. She’s wearing a neon-green plastic circle around her neck and rainbow clown hair. She grins. “Put your shoes on and come out front.”

Outside we’re met by a scene that seems straight out of those bad acid trips you see in the movies: the Stanford marching band in what appears to be mostly their underwear and glow-in-the-dark necklaces and bracelets and stuff, rocking their respective instruments, trumpets blaring, drums beating, cymbals crashing, the school mascot in his big green pine tree costume zooming around like a crazy man, a bunch of half-dressed, partially glowing students jumping and bumping and whooping and laughing. It’s incredibly dark, like they’ve turned out the streetlights for the occasion, but I search for Angela and spot her looking supremely annoyed, standing next to two blond girls—her roommates, I assume. I weave my way over to them.

“Hi!” Angela yells. “You have bed hair.”

“This is insane!” I shout, combing through my hair with my fingers, with little success.

“What?” she screams.

“Insane!” I try again. It’s so unbelievably loud.

One of Angela’s roommates gapes and points behind me. I turn to see a guy wearing a Mexican-style wrestling mask that covers his entire face. A shiny gold wrestling mask. And nothing else.

“My eyes, my eyes!” Angela shrieks, and we all start giggling hysterically, and then the song is over, and we can hear again, and they’re telling us to run.

“Run, little freshmen, run!” they scream, and we do, like a herd of confused, stampeding cattle in the dark. When we finally stop, we’re at the next dorm over, and the band starts up again, and pretty soon another crowd of bleary and baffled freshmen begins to filter out of the doors.

I’ve lost Angela. I look around, but it’s too dark and the crowd is too big to find her. I make out one of her roommates standing a few feet away from me. I wave. She smiles and pushes her way over to me like she’s relieved to see a familiar face. We bob halfheartedly to the music for a few minutes before she leans over and yells next to my ear, “I’m Amy. You’re Angela’s friend from Wyoming?”

“Right. Clara. Where are you from?”

“Phoenix!” She hugs her sweatshirt tighter around her. “I’m cold!”

Suddenly we’re moving again. This time I make it a point to stay close to Amy. I try not to think about how this feels eerily similar to my vision in some ways, running around in the dark, not knowing where I’m going or what I’m going to end up doing. It’s supposed to be fun, I know, but I find this whole thing a bit creepy.

“Do you have any idea where we are?” I pant out to Amy the next time we stop.

“What?” She can’t hear me.

“Where are we?” I yell.

“Oh.” She shakes her head. “No clue. I’m guessing they’re going to make us run all the way across campus.”

I remember how on the tour they told us that Stanford has the largest campus of any university in the world aside from one in Russia.

It could be a long night.

There’s still no sign of Angela or the other roommate, who Amy tells me is named Robin, so Amy and I stick together and dance and laugh at Naked Guy and shout out a conversation the best we can. In the next half hour here’s what I find out about Amy: we were both raised with single mothers and little brothers, we’re both thrilled that tater tots are served at breakfast in the Roble dining hall every morning and horrified at how tiny and claustrophobic the shower stalls in the bathrooms are, and we both suffer from annoyingly unruly hair.

We could be friends, I realize. I could have made my first new friend at Stanford, just this easily. Maybe there’s something to this making-us-run thing.

“So what’s your major?” she asks as we’re jogging along.

“Undecided,” I answer.

She beams. “Me too!”

I’m liking her more and more. But then disaster strikes. As we come up on the next dorm, Amy stumbles and falls. Down to the pavement she goes, all flailing arms and legs. I do my best to make sure she doesn’t get trampled by the ever-growing stream of scrambling freshmen, then drop to the sidewalk next to her. It’s bad. I can tell just by looking at her white face and the way she’s clutching her ankle.

“I stepped wrong.” She groans. “God, this is embarrassing.”

“Can you stand up?” I ask.

She tries, and her face gets even whiter. She sits back down heavily.

“Okay, that’s a no,” I deduce. “Don’t go anywhere. I’ll be right back.”

I mill around looking for someone who seems even a little bit helpful and miraculously spot Pierce at the edge of the crowd. Time to put his “dorm doctor” skills to good use. I run over to him and touch him on the arm to get his attention. He smiles when he sees me.

“Having fun?” he yells.

“I need your help,” I yell.

“What?” he yells.

I end up taking him by the hand and dragging him over to Amy and pointing at her ankle, which is starting to swell. He spends several minutes kneeling beside her, gently holding her ankle between his hands. Turns out that he’s premed.

“It’s probably a sprain,” he concludes. “I’ll call someone to give you a ride back to Roble, and we’ll get it elevated and put some ice on it. Then you should go to Vaden—the student clinic—in the morning, get an X-ray. Just hang in there, all right?”

He walks off to find somewhere quieter to use his phone. The band finishes its song and moves on, leading the crowd away from us in a rumble of feet. Finally I can hear myself think.

Amy starts to cry.

“I’m so sorry,” I say, sitting down next to her.

“It doesn’t hurt that much,” she sniffles, wiping at her nose with the back of her sweatshirt. “I mean, it hurts—a lot, actually—but that’s not why I’m crying. I’m crying because I did something so totally stupid like wear flip-flops when they told us to put on shoes, and this is only the first week of school. I haven’t even started classes yet, and now I’m going to be hopping around on crutches, and everyone’s going to label me as that klutzy girl who hurt herself.”

“Nobody will think less of you. Seriously,” I say. “I bet there are plenty of injuries happening tonight. It’s all pretty crazy.”

She shakes her head, sending a tumble of wild blond curls over her shoulders. Her lip quivers. “This is not how I wanted to start things,” she chokes out, and buries her face in her hands.

I glance around. The group has moved far enough away that we can only faintly hear them. Pierce is standing next to the building with his back to us, talking into his cell. It’s dark. No one’s around.

I lay my han

d gently on Amy’s ankle. She tenses, like even this light touch is hurting her, but doesn’t lift her head. Through my empathy I can feel the hurt in her, not only the way she’s mentally beating herself up over how she’s already ruined her reputation, but the physical part, too, the way the ligaments in her ankle are pulled away from the bone. It’s a bad injury, I know instantly. She could be on crutches all semester.

I could help her, I think.

I’ve healed people before. My mom after she was attacked by Samjeeza. Tucker after our post-prom car accident last year. But those times I had the full circle of glory around me, the whole shebang, light emanating from my hair, my body glowing like a lantern. I wonder if there’s a way to localize the glory to just, say, my hands, to channel it fast so that nobody will notice.

I clear my head, glad for the relative quiet, and focus my energy on my right hand. Just the fingers, I think. All I need is glory in my fingers. Just once. I concentrate on it so hard that a bead of sweat moves along my hairline and drips down onto the concrete, and after a few minutes the very tips of my fingers start to glow, dimly at first and then more brightly. I press my hand firmly to Amy’s ankle. Then I send the glory out of me like a trickle of light spreading from me to her, not too much or too fast but hopefully enough to do some good.

Amy sighs, then stops crying. I sit back, watching her. I can’t tell if what I did helped at all.

Pierce comes back over, looking apologetic. “I can’t find anyone to come get you. I’ll have to run and get my car, but it’s on the other side of campus, so it will take a while. How are you doing?”

“Better,” she says. “It doesn’t hurt as much as before.”

He kneels down next to her again and examines her ankle. “It looks better, actually, not as swollen. Maybe you just twisted it. Can you try to walk?”

She gets up and gingerly puts her weight on her injured foot. Pierce and I watch as she limps a few steps, then turns back to us. “It feels okay now,” she admits. “Oh my God, am I a drama queen or what?” She laughs, her voice full of relief.

“Let’s get you back to your room,” I stammer out quickly. “You still need to put some ice on that, right, Pierce?”

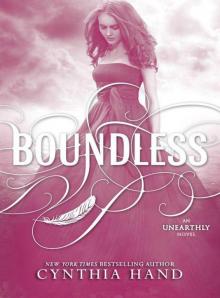

Boundless

Boundless My Plain Jane

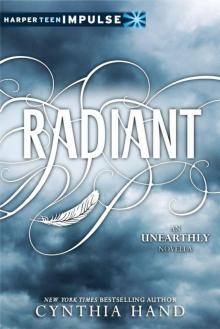

My Plain Jane Radiant

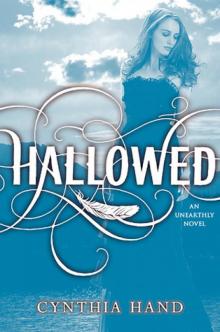

Radiant Hallowed

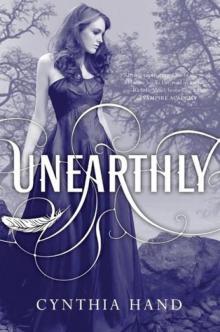

Hallowed 01 Unearthly

01 Unearthly My Lady Jane

My Lady Jane My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Unearthly

Unearthly The Last Time We Say Goodbye

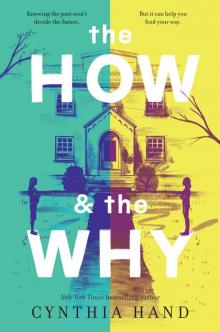

The Last Time We Say Goodbye The How & the Why

The How & the Why Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse)

Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse) Unearthly u-1

Unearthly u-1 Boundless (Unearthly)

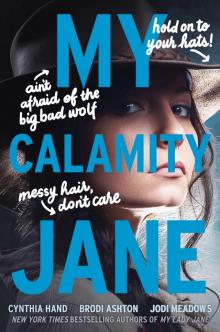

Boundless (Unearthly) My Calamity Jane

My Calamity Jane Hallowed u-2

Hallowed u-2 Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel

Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel