- Home

- Cynthia Hand

The How & the Why

The How & the Why Read online

Dedication

For Mom and Dad, who didn’t ask for a refund

even though I was clearly a faulty baby.

And for the anonymous girl who put me into their arms.

Thank you.

Epigraph

I love you because the entire universe

conspired to help me find you.

—PAULO COELHO

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Epilogue: Six Months Later

Note from the Author

About the Author

Books by Cynthia Hand

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Dear X,

Today Melly has us writing letters to our babies.

I’m not keeping you, so this felt like cruel and unusual punishment. There are fifty girls at this school, and only a few of us are choosing adoption, and most of those are open adoptions, where everyone knows each other’s names and you send emails back and forth to the new parents and get pictures and an update every month or something. But I’m not doing that, either.

So I said I’d like to opt out of this assignment.

Melly said fine, I could opt out if I wanted to, but then she said that there’s a program where you write a letter to your baby, which they can request when they turn eighteen. So if there’s something you want to say that can’t be done by checking a box or writing down your blood type, here’s your chance.

“You can write whatever you want,” Melly said. “Anything.”

“But it’s optional, right?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Which means I don’t have to do it.”

“Okay,” Melly said. “You just sit here and chill.”

Then she passed around some yellow notepads, like legal ones (which seems kind of old school if you ask me) and she gave one to me, too. “Just in case,” she said. Sneaky Melly.

The other girls started scribbling away. Apparently they all have important things to tell their babies.

Not me. No offense, but I don’t even know you that well.

To me, you’re still sort of intangible. I know you’re in there, but you’re not obvious yet.

You’re tight pants.

You’re heartburn.

You’re the space alien slowly taking over my body.

You’re X.

I can’t imagine you as an actual baby, let alone an eighteen-year-old person reading this letter. I’m not even eighteen yet myself.

So what could I possibly have to say to you? I don’t have any great wisdom to pass along that couldn’t be summed up by the words use birth control, girls. But that’s complicated, because if I’d done that, you wouldn’t exist. I’m sure you prefer existing.

Some things are better left unsaid, was my thinking. So I sat there, chilling. Not writing a letter.

But obviously I changed my mind.

I started to consider you, I guess. If I were an adopted kid, I’d want there to be a letter for me. Because I’d want to find out the things that aren’t in the paperwork. I’d be curious. I’d want to know.

So . . . hi. I’m your birth mother, aka the person who lugged you around inside of me for nine months.

I have blue eyes and brown hair and I’m a Libra, if you’re the kind of person who’s interested in signs. There’s not much more to tell about me, I’m afraid. I’m solidly average—sorry, I wish I could report that I’m a genius or gorgeous or spectacularly gifted at the piano or chess. But I’m just typical. My grades aren’t fantastic. I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up. I’m not a cheerleader. I don’t do sports.

I am into music. I collect old vinyl records. I go to concerts, music festivals, that kind of thing. I follow some of the local bands.

Right now I’m living at Booth Memorial, a place where pregnant teens go to finish high school. It’s a school, but it’s also a group home—like in those days when girls used to disappear for months and their parents would tell everybody they were “visiting an aunt.” Most of the homes for unwed mothers around the country have closed, since having a baby out of wedlock isn’t the super shocking thing it used to be. This place is mainly a school now. A few of us live here, but the majority of the students live at home, and, like I said, they’re keeping their babies. There’s a daycare on campus where they can bring them after they give birth.

I guess you must be wondering why I’m not keeping you. The simplest answer is this: I’m not cut out to be a mother.

Not that I’m a terrible person. But I’m sixteen years old. I don’t think anybody is exactly qualified to be a mother at sixteen. I’m trying not to be judgmental, but the girls around here, the ones who are keeping their babies and who look at me like I’m some kind of monster because I’m not keeping mine, they think it’s going to be sharing clothes and braiding each other’s hair and being BFFs. But that’s not the real world.

The real world. God, I sound like my father. He would not approve of this letter-writing thing. Dad’s a believer in the clean-slate philosophy. “After this, you can start over,” he keeps telling me. “You can wipe the slate clean.”

What he doesn’t say, but I hear anyway, is, “And then nobody will have to know.”

So here I am, hiding out like it’s the fifties. At school—at my old school, I mean—nobody knows about my predicament except my best friend. I’m sure people are asking her where I am. I don’t know what she tells them. But maybe it’s easier being here than parading my pregnant belly through the halls of BHS. It’s less to deal with, anyway.

The point is, I hope you get it—the why of the whole thing. I hope you have a good life—a boring, no-drama, no-real-problems kind of life.

Good luck, X. I wish you the best.

Your host body,

S

1

“Happy birthday, Cass,” says Nyla.

“Thanks.” I dunk a chip into the salsa and eye the mariachi band singing in the corner of the restaurant. I hope Nyla didn’t tell them it’s my birthday.

“So how does it feel,” she asks, “the great one eight?”

I shrug. “It’s not a big deal.”

“Not a big deal?” she scoffs. “But now you can buy cigarettes.”

“Ew.” I crunch the chip. “Like I would ever.”

“Agreed—ew—but you can do so much now,” she elaborates. “You can purchase lottery tickets. You can op

en your very own bank account, or get a tattoo. You can drink alcohol in Europe.”

“Yeah, I’ll get right on that.”

“My point is, now you’re a grown-up.” She leans forward across the table, like she’s about to impart some secret of the universe. “You’re an adult,” she whispers.

I lean forward, too. “I kind of liked being a kid.”

She sighs and sits back. “Boo. You’re no fun.”

“You’re just jealous because you’re not going to be eighteen for another twenty-nine days.” I love lording it over Nyla that I’m exactly one month older than she is. And therefore wiser.

She scoffs. “When we’re forty you’re going to wish you were the younger one.”

“When we’re forty, I definitely will.” I grin. “But right now I’m happy to be your elder.”

She sticks her tongue out at me.

“Hey, now. Respect your elders,” I scold her, and she rolls her eyes.

I check my watch. It’s seven thirty. Still time to sneak in to see Mom. “We should get going,” I start to say, but at that moment the mariachi guys show up to serenade me with “Happy Birthday” in Spanish. Nyla sings along as I glare at her. The waitress plops a giant serving of fried ice cream down in front of me, a single candle burning in the middle.

Everyone in Garcia’s turns to look.

“Oh wow . . . thank you . . . so much.” I blow out the candle and push the bowl of melty ice cream into the middle of the table so Nyla can share. “I hate you, by the way.”

“No, you don’t.” She licks ice cream off her spoon. “I’m pretty sure you love me.”

“Fine, I love you,” I grumble. I notice that the elderly couple at the next table over is not-so-subtly staring at Nyla. It happens. Occasionally people in this white-bread Idaho town act surprised when they see a black person. It’s what Nyla calls the unicorn effect. People see her and stare like she’s some rare and magical creature that they’ve only heard about in storybooks. Which is weird for Nyla, because she was raised by a white family in a white town and doesn’t totally identify as American Black.

We ignore the gawkers and polish off the rest of the ice cream. Nyla gestures at the waitress for the bill. Which she pays. She always pays, birthday or not. I try not to feel guilty about it.

“Dinner was excelente,” I say as we walk out to Bernice, Nyla’s car. “Gracias, señorita.”

“De nada,” Nyla replies. Yay for three years of middle school Spanish. This is unfortunately about the collective sum of our ability in that language.

We climb into the car. “Seat belts,” Nyla says primly, and we’re off.

I get the sensation that we’re sailing instead of driving, which is normal. Bernice is a boat. She’s named after Nyla’s grandma, because she’s a total grandma car—silvery blue and enormous and built like a tank. But Bernice always gets us where we need to go.

“On the road again,” Nyla sings as we’re cruising along through Idaho Falls.

“Just can’t wait to get on the road again,” I join in.

I check my watch. Seven forty. Still time. Then I realize we’re heading in the opposite direction of home. “Hey, where are we going?”

“Oh, I thought we could take a drive,” Nyla says mysteriously.

Like this is something people do: take drives. “A drive where?” I ask as we turn onto Hitt Road. Hitt Road, I think for more than the hundredth time, is an epically bad name for a road. Why not call it Smash Street? Insurance Claim Lane?

Nyla glances in the rearview mirror. “To Thunder Ridge.”

“Um . . . why?” Thunder Ridge is a hill that overlooks the city. As far as I know, making out is about all people do there.

“It has a nice view,” Nyla says. “I thought we could hang out a bit. Talk.”

“We’ve been talking all day. That’s practically all we do, is talk.”

“Cass.”

“Nyla.” I give her a look. “What’s going on?”

“Nothing. Can’t a girl take her bestie to a quiet spot to contemplate the meaning of life and birthdays?”

“I guess, but you know my dad has that birthday tradition where he tells me the story of the day they got me, and we look at my baby book, and there’s me in a bunch of frilly pink dresses, and I want to vomit, but I also kind of love it? I don’t want to miss that.”

“You won’t miss it.” She’s got her phone out now. She’s driving and texting. She knows I loathe driving and texting. I hate texting, period, especially when you’re supposed to be having real time with someone. It’s important to be present, my mom always says. And, come to think of it, Nyla was texting all through dinner. Which is not normal Nyla behavior.

“Ny, come on,” I say. “What’s going on?”

“Nothing,” she says, and then suddenly changes her mind: “You’re right. Thunder Ridge is a silly idea. I’ll take you home.”

She pulls into a subdivision and then flips a U at the entrance and turns us around.

We drive back toward our part of town.

“Country roads, take me home, to the place I belong,” Nyla sings.

I don’t sing along this time. I’m confused. I feel like I’m failing at some kind of crucial friend test. We stop at a light, and Nyla finishes singing John Denver. She looks at her phone. Touches up her lipstick in the mirror. Checks her phone again.

“Is there something you specifically want to talk about?” I ask. “Because I can talk.”

“Nah, I’m good,” she says. But obviously she’s still being weird.

“I do love our meaning-of-life conversations.”

She smiles. “Me too.”

“I’m here for you.”

“I know.”

“So . . . you can talk if you need to talk. I’m listening. I swear.”

She seems to consider this for a minute, and then she says, “I can’t think of anything to say. Besides, we’re almost there.”

We are. Bernice veers off into my neighborhood. There are a bunch of cars parked along the street in front of my house. Nyla has to park a little ways down.

“You want to come in for a minute?” I ask. “We could—I don’t know—talk?”

She smiles. “Did you know that now you’re eligible for jury duty? You can be called upon anytime, and you have to do it.”

And yay, we’re back on the subject of being eighteen again. I make a face. “Excellent.”

“Plus, now you can vote.”

“I can’t wait.”

“You can enlist in the army,” she adds as we make our way up the sidewalk and onto my front porch.

“No, thank you.” I gaze at my house. The windows are dark—the living room curtains drawn. I wonder if Dad’s already at the hospital.

“You can buy fireworks,” Nyla continues. “Or go skydiving. Or go to real-people jail.” She gasps and grabs my arm. “You can get married without the permission of your parents!”

I arch an eyebrow at her. “That’s great news, Ny. Too bad I’m single.” She knows this. She also knows that I don’t plan to get married until I’m at least twenty-five. “Though speaking of which, there is one thing I do want to do,” I say as I fumble with my keys at the front door. “Now that I’m officially eighteen.”

“Oh yeah?” Nyla cocks her head at me, her curly hair like a dark halo around her head. “Don’t tell me you want to get your belly button pierced. Because I do not approve.”

“Ouch. No.” The lock clicks and the door swings open, but I stop and turn to face Nyla. “I want to have sex,” I announce. “I think it’s time. I’m ready.”

I don’t know why I say it like that. It’s not really the sex part I’m ready for, exactly. It’s the boyfriend part. I’m eighteen now, and I’ve never had a real boyfriend. I’ve gone on a few dates here and there, kissed a guy or two, made out a little, but I’ve never been in love, never felt that way about anybody. But somehow it’s easier to talk about sex than it is to confess that I want to fall in

love, which sounds cheesy. It’s also fun to say something shocking to Nyla every now and then. Which totally worked; she’s frowning, staring past me over my shoulder into the dark house like she wants to go inside. “Uh, Cass—”

“I mean, obviously I don’t want to have sex just for the sake of having sex,” I clarify. “That’s stupid. I know. I want to be a responsible adult now that I’m actually an adult. I would want it to be with the right guy. And maybe the right guy won’t come along this year, because—come on, do we know any guys who are, like, boyfriend material? Not really, right? And I’m okay with that.”

“Okay . . .” Nyla still looks super uncomfortable.

“All I’m saying is, if the right guy does come along, I’m open to the idea of having sex.”

That said, I turn to go into the house and almost run smack into my dad inside the doorway. He’s wearing a paper party hat. Holding a flaming birthday cake. Surrounded by my grandma and my uncle Pete and, like, ten of my friends.

“Surprise?” my dad whispers.

“Oh my God.”

“Yeah,” he says. “Yeah, I know.”

“You were all standing here.”

He gives a painful smile. “We were.”

“I say go for it, honey,” says Grandma. “Seize the day.”

“I’m a big no on this one,” says Uncle Pete. “No sex for you. Possibly ever.”

“Wait, how am I not considered boyfriend material?” says my friend Bender. “I’m, like, hot.”

“Does this mean I’m going to need a shotgun?” asks Dad.

I’m humiliated for all of five seconds. But then Nyla starts giggling, which makes me start giggling, and then we’re all outright laughing, then singing, and then I blow out the eighteen candles on the cake.

2

“Was it a good cake?” Mom asks later, at the hospital.

“It was grocery store cake.” I sit on the edge of the bed and rub her feet under the covers. Even through the blankets they feel like blocks of ice. “Dad can’t make himself go to the shop.”

“I miss it.” Mom sighs. “I miss everything.”

I nod. “I used to think the shop was actual magic.”

“It was,” Mom agrees, but then she does that thing where she makes a conscious choice not to dwell on what she’s lost. “So. Happy birthday. I’m sorry I couldn’t be there for your party.”

Boundless

Boundless My Plain Jane

My Plain Jane Radiant

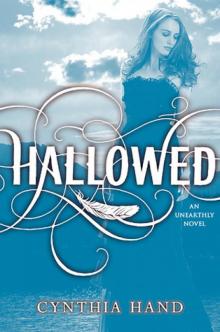

Radiant Hallowed

Hallowed 01 Unearthly

01 Unearthly My Lady Jane

My Lady Jane My Contrary Mary

My Contrary Mary Unearthly

Unearthly The Last Time We Say Goodbye

The Last Time We Say Goodbye The How & the Why

The How & the Why Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse)

Radiant (HarperTeen Impulse) Unearthly u-1

Unearthly u-1 Boundless (Unearthly)

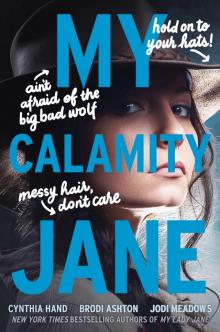

Boundless (Unearthly) My Calamity Jane

My Calamity Jane Hallowed u-2

Hallowed u-2 Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel

Hallowed: An Unearthly Novel